Introduction

In this post, I will introduce you to the Young Ottomans. Even though the Young Turks, the political movement that orchestrated the 1908 Revolution and governed the Empire until its final days in 1922, are relatively well known in the West, the same cannot be said of the group that could be perceived as their predecessors.

Defined as “the first modern-style opposition movement among Ottoman intellectuals,”1 the Young Ottomans consisted of a new breed of intellectuals who were very much a product of their time. Having received their education in the new schools established in the 19th century, the Young Ottomans held a sharp critique of the Ottoman bureaucrats ruling the Empire at the time. In voicing their opinions, they made effective use of new forms of media, such as newspapers, which gradually came to play a significant role in the Ottoman political scene. What made the Young Ottomans even more unique, however, was their ability to engage equally well with modern liberal ideas and traditional Islamic thought.

I will structure the post in three main parts. First, I will give you the historical background from which the Young Ottomans emerged and introduce you to the group as a whole, while also examining some of their common concerns. Then, I will zoom in on Namık Kemal, who was arguably the group’s most famous member. Finally, I will wrap the article up by taking a brief look at the historical legacy that the Young Ottomans left behind.

The Tanzimat and the Emergence of Young Ottomans

As I have written before, the Tanzimat period was characterized by a number of key themes. First, it was defined by two imperial edicts, the Gülhane Edict of 1839 and the Reform Edict of 1856, which paved the way for ensuring the equality between Muslims and non-Muslims of the Empire while also laying the groundwork for the birth of a cosmopolitan Ottomanist ideology.

The period also witnessed the shift of the center of power from the Ottoman Palace to the Sublime Porte, traditionally the seat of the Ottoman vizier and, during the Tanzimat, the nerve center of the Ottoman bureaucracy. With the death of Sultan Mahmud II, Ottoman bureaucrats, such as Mustafa Reşit, Ali, and Fuat Pashas, took the reins of power in the Empire and reigned almost unchecked, implementing their modernizing agenda that transformed the Empire.

The reforms, which started to be implemented in the late 18th century and solidified during Mahmud II’s reign, accelerated in this period. New schools based on modern/Western curricula continued to be established all over the Empire, leading to an increase in the literacy rate and the emergence of a reading public. Although an official newspaper, called Takvim-i Vekayi (“Calendar of Affairs”), had already been established in 1831, privately owned newspapers started to proliferate from the mid-1860s onwards. As a result, a vibrant public sphere began to emerge, where political, cultural, and social issues were discussed, and new ideas were introduced to the population at large. Equally importantly, these newspapers also opened up different streams of income for Ottoman intellectuals, who, at least theoretically, did not have to depend on securing a position within the bureaucracy to be able to make a living anymore, as was traditionally the case.

Meanwhile, the graduates of the modern schools were trained in European languages, particularly French. Through their newly acquired language skills, they could follow the most current political and social debates that were going on in Europe at the time. Some of the students were also sent to Europe to study and had the opportunity to experience life there firsthand. The same was also true for the young generation of Ottoman diplomats who represented the Empire in European capitals, where they had front-row seats to the machinations of European politics.

The Young Ottomans were a product of this rapidly changing political, cultural, and social environment. Their origins go back to 1865, when they first came together to demand a constitutional government. Their activities really took off, however, when they found a patron in Mustafa Fazıl Pasha, the brother of Ismail Pasha, the viceroy of Egypt.

Mustafa Fazıl had good reasons to bankroll a movement that opposed the Ottoman government, as he wasn’t very happy with it himself. In 1866, his brother convinced Sultan Abdulaziz (mostly through bribes) to change the hereditary system of succession in Egypt from seniority to primogeniture, while also giving him the title of “khedive.” This move effectively barred Mustafa Fazıl Pasha from becoming the next khedive. In response, Mustafa Fazıl Pasha moved to Paris and began campaigning against the Ottoman government, inviting the Young Ottomans to join him

The Young Ottomans, under pressure from the Ottoman government, accepted Mustafa Fazıl Pasha’s offer. From exile, they began to propagate their ideas through the newspapers they founded, almost all of which were bankrolled by Mustafa Fazıl Pasha and smuggled into the Empire to escape Ottoman censorship.

Although they never had a coherent internal structure or a program, the Young Ottomans had several common concerns that they addressed in their writing:

1) Dissatisfaction with the higher echelons of the Ottoman bureaucracy and how they ran things in the Empire, especially with regard to foreign intervention and the Empire’s finances,

2) A demand for adopting a constitution and shifting the Empire towards a constitutional monarchy, which, they believed, would ensure unity among the Ottomans.

3) A critique of the Tanzimat reforms, some of which the Young Ottomans believed were too “Western.” While they were not a “reactionary” movement per se and engaged closely with liberal ideas, the Young Ottomans argued that Islam should continue to be a constitutive framework in the future of the Empire.

Namık Kemal: An Ottoman Patriot

As a group, the Young Ottomans included several key intellectuals who greatly influenced Ottoman political thought from the 1860s onward, such as Ziya Pasha, Ali Suavi, and Ibrahim Sinasi. If there was one figure, however, who could be described as the epitome of Young Ottomans, it was Namık Kemal.

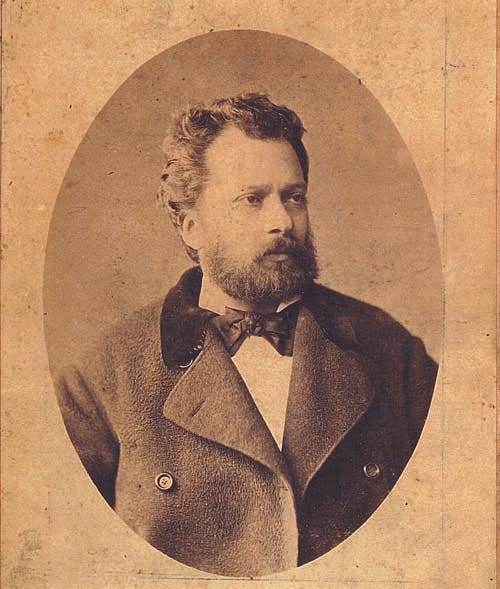

Namık Kemal was “a poet, playwright, and political essayist who espoused the cause of reform and the ideas of patriotism, Ottomanism, and Pan-Islamism.”2 Born in 1840 to a family that belonged to the higher echelons of the Ottoman bureaucracy, Namık Kemal began serving as a civil servant in the Translation Office in 1859, where he honed his skills in European languages. It was also during this time that he began to pursue poetry seriously, the genre in which every budding Ottoman intellectual aspired to be successful. Before he accepted Mustafa Fazıl Pasha’s invitation, Namık Kemal had also been working in the newspaper Tasvir-i Efkar (Description of Ideas), where he wrote on a number of social and political issues.

During his days of exile in Paris, London, and Vienna, Namık Kemal translated into Ottoman Turkish the works of European thinkers such as Victor Hugo and Jean Jacques Rousseau, who had a major influence on his political views. He also established a newspaper called Hürriyet (“Freedom”). In 1871, he returned to Istanbul and started publishing another newspaper, Ibret (Warning), where he continued to espouse his political ideas.

It was around this time that he wrote his most famous play, Vatan Yahut Silistre (Fatherland; or Silistria, 1873), one of the most important literary works of its time that advocated for a sense of Ottoman patriotism. The play was a major success, but it also provoked the ire of the Ottoman bureaucrats, as well as Sultan Abdulaziz. This was mainly because it strongly emphasized Islam’s role as the primary frame of reference in the Empire, which was a direct challenge to the egalitarian Ottomanist ideology that the government strived to propagate at the time. As a result, Namık Kemal was exiled once again. Later in his life, he was pardoned by Sultan Abdulhamid II, who commissioned him to draft the new Ottoman constitution, which was proclaimed in 1876.

It was fitting for Namık Kemal to be chosen as one of the figures commissioned to draft the new Ottoman constitution because the need to transform the Ottoman Empire into a constitutional monarchy was one of the cornerstones of his political ideology.

Namık Kemal was a proponent of Ottomanist ideology, arguing that Ottomans from every religious and ethnic background belonged to the Ottoman political entity. In this vein, he also believed “that an Ottoman representative assembly would serve as a powerful unifying force for the Ottoman lands.”3 However, he did not approach the issue from purely a Western liberal perspective. Instead, he grounded his advocacy of constitutionalism and representative assembly on an Islamic framework.

His defense of constitutional monarchy and popular sovereignty, for instance, borrowed idea of “biat,” an Islamic term meaning an oath of allegiance to a ruler, “with the annulling of the biat being society’s rightful recourse against a corrupt or incompetent ruler.”4 In this framework, the electoral vote represented a way for the population to demonstrate their “allegiance” to the rulers, which could be rescinded if they were not happy with the way they governed.

Namık Kemal was also known for having introduced concepts such as “vatan” (fatherland) or “hürriyet” into the Ottoman political discourse. Before he instilled them with political connotations, these words had different meanings in Ottoman Turkish. “Vatan,” for instance, simply meant where a person was from, having a more localized meaning. In the way Namık Kemal used it, the word came to mean the “fatherland” (meaning the Empire as a whole), to which all Ottomans belonged. Meanwhile, “hürriyet” had the narrow meaning of being free of slavery before it came to mean “freedom” in a political and liberal sense.

The Legacy of the Young Ottomans

On the whole, it may be argued that the Young Ottomans were more of a “cultural” rather than a political movement. Attempting to bring together modern liberal ideas with traditions of Islamic thought, their primary goal was to “create a new Ottoman culture that would be modern without sacrificing its identity to Westernization.”5 They could not, however, square the circle and solve the identity crisis that the Empire was going through at the time. Nor could they establish a successful modus operandi between the encompassing, cosmopolitan ideology of Ottomanism and a framework that positioned Islam as the foundation of Ottoman body politic. This existential angst would continue to haunt the Ottoman intellectuals until the final days of the Empire.6

On the other hand, the vocabulary they introduced into the Ottoman political discourse would continue to exert its influence on generations of Ottomans to come and even beyond. The Young Turks, for instance, would make the notions of freedom from tyranny and the need for a constitutional government a rallying cry for their own opposition against Sultan Abdulhamid II. Mustafa Kemal was also a fan of Namık Kemal’s poems during his days in the Military Academy.7 Even today, the works of Namık Kemal, with their strong emphasis on the love of the fatherland, are still taught in schools in Turkey.

Finally, the way the Young Ottomans grounded liberal principles on Islamic terminology while advancing their arguments represented an early form of Islamic modernism. Even though definite connections have not been established, the Young Ottomans’ attempts to reconcile Islamic principles with modern ideas would find their echoes in the works of Muslim intellectuals such as Muhammad Abduh and Rashid Rida, who would go on to become very influential in the Muslim world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Thank you very much reading. If you enjoyed this post, please consider hitting the “heart” button and sharing it with anyone who might be interested. And if you’d like more articles on the history of the Ottoman Empire, please subscribe to this newsletter.

Carter Findley, Turkey, Islam, Nationalism, and Modernity: A History, 1789-2007, Yale University Press, 2010, 104.

“Namık Kemal” in Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire, eds. Gabor Agoston and Bruse Masters, Facts on File Press, 2008, 417.

Ibid., 418.

Ibid.

Findley, Turkey, Islam, Nationalism, and Modernity, 105.

Ibid., 105-106.

Ibid., 124.

Central piece of contemporary history!!! Thank you!!!

Thanks once again for the interesting history of the Ottoman empire an important European neighbour and rival. We unfortunately see mostly a balding ex football player taking it and use it to throw his weight around