Who was Mustafa Kemal Atatürk?

A review of Şükrü Hanioğlu’s Ataturk: An Intellectual Biography

On 29 October 2024, Turkey commemorated the 101st anniversary of the founding/establishment of the Turkish Republic, and today, November 10, 2024, marks the death anniversary of the key historical figure who made it possible: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

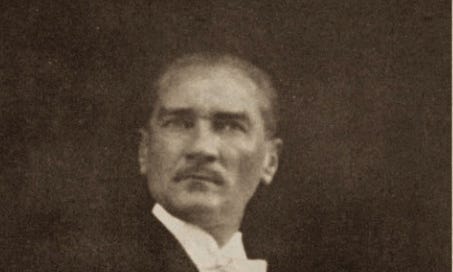

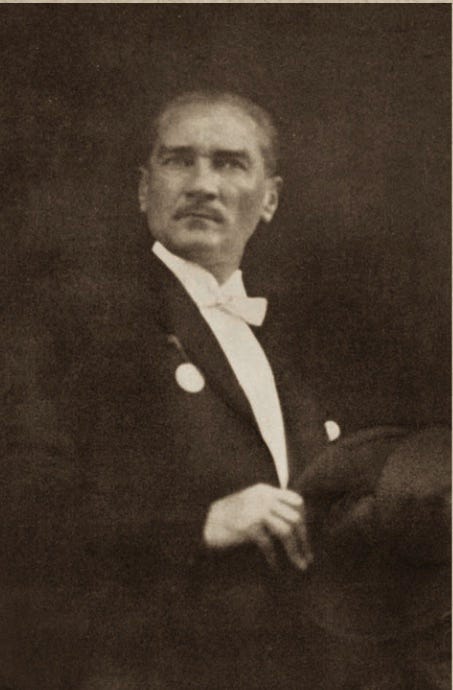

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s life is well known. He was an Ottoman general who played a major role in the Turkish War of Independence, fought between 1919 and 1922 against the Allies, who invaded the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of World War I. He is also known as the great reformer and founder of modern Turkey, who undertook sweeping Westernizing reforms that put the country on the path of “civilization.”

Mustafa Kemal’s life is also wrapped up in nationalist hagiography, however, especially in modern Turkish historiography. In most accounts, he is generally presented as a mythical, larger-than-life figure who almost stood outside of history.

Within this context, historian Şükrü Hanioğlu’s Ataturk: An Intellectual Biography is a rather welcome addition to the literature. Bringing a fresh perspective, it depicts Mustafa Kemal very much as a man of his time and helps us understand how he came to be who he was. In the book, Hanioğlu aims to demythologize, historicize, and contextualize Mustafa Kemal, basing his analysis on a variety of primary sources, including Mustafa Kemal’s speeches, his personal notes, and the books he read throughout his life.

Hanioğlu has three goals for his work. First, he situates Mustafa Kemal firmly in a historical context. He argues that even though Mustafa Kemal’s role in establishing a new nation-state out of the ruins of the Ottoman Empire obviously can’t be ignored, he was still an “intellectual and social product of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.”1 Contrary to how a major part of the Turkish historiography depicts him, Mustafa Kemal “should not be viewed as a solitary genius impervious to his upbringing, early socialization education, institutional membership, social milieu, and intellectual environment,”2 all of which shaped him to a great extent.

In addition to placing Mustafa Kemal into his historical context, Hanioğlu also traces his intellectual development, which is important for understanding his future policies as the leader of modern Turkey. Finally, through a study of Mustafa Kemal’s “life, ideas, and work,” Hanioğlu provides a study of the transition from the late Ottoman order into the modern Turkish Republic, arguing that this move represented continuity and not a total break from the past.

Mustafa Kemal was born in Salonica in 1881. The city, located in modern-day Greece, had a major impact on his later worldview. According to Hanioğlu, Mustafa Kemal’s westward orientation first developed during the childhood that he spent there.

The Tanzimat was a period of rapid transformation for the Ottoman Empire, where “modernity” and “tradition” existed side by side in Ottoman society. Growing up in Salonica, Mustafa Kemal had the opportunity to make a comparison between the traditional way of life and the new and modern one. He opted for the latter. For his early education, he attended modern schools that had been newly established in the city from the mid-19th century onward and taught a Western curriculum. This early educational background had an impact on Mustafa Kemal’s worldview in the years to come.

The city shaped him in other ways, too. It was during his years in Salonica that Mustafa Kemal first started developing a sense of enmity against European economic domination, which would become one of the hallmarks of his policies once he became the leader of modern Turkey. This aversion towards outside intervention stemmed mainly from his witnessing the gradual transfer of economic power from Muslims to non-Muslims at this time, with the non-Muslim bourgeoisie taking advantage of the backing of European powers to further their own interests. He even had a personal example in this vein with his father’s business suffering because of the Greek brigands who were in collaboration with the non-Muslim merchants.

After graduating from the military preparatory school in Salonica and the military high school in Monastir, Mustafa Kemal went to Istanbul and enrolled in the Royal Military Academy. This was the next major step in his intellectual development. The Academy trained the future military elite of the Empire and it was here that Mustafa Kemal was further exposed to new ideas that would go on to shape the way he perceived the world and his role in it.

One such idea that had an impact on Mustafa Kemal to a great extent was the notion of “Das Volk in Waffen” (The Nation in Arms). Advanced by the German military theorist Colmar von der Goltz, who had been invited to reform the Ottoman Royal Military Academy in 1883-1884, it argued that the war in the modern age was not only a war between armies but a war between nations. In this type of war, von der Goltz claimed, it fell upon the military elite to lead the nation.

By the time Mustafa Kemal enrolled in the Academy, von der Goltz’s idea of a “Nation in Arms” had become the dominant paradigm, according to which the institution was producing a new class of officers who were instilled with the idea that they were responsible for the advancement of the Ottoman nation. After the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, this idea found itself on fertile ground when the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) toppled Sultan Abdulhamid and took the reins of power. Many of the CUP leaders were themselves graduates of the Academy and believed in the military’s role in the Empire’s modernization and survival. Although Mustafa Kemal was not a leading figure in the CUP at this time, he shared many of their beliefs when it came to the role that the military elite should play in the Empire’s future.

Supplementing this notion of a “Nation in Arms,” the other framework Mustafa Kemal embraced at this time was elitism. Hanioğlu argues that the members of the new military elite felt they were different from the masses with their Westernized ways. They were also elitist. Influenced to a great extent by Gustave Le Bon, whose views were popular among the Ottoman intelligentsia at the time, the members of the military caste perceived themselves as above the rest of society, with an almost natural right to govern the people.

Le Bon’s ideas had an impact on Mustafa Kemal. Born and raised in the Rumelian provinces of the Empire, he already had a sense of belonging to a “privileged caste.”3 Reading Le Bon, he came to believe that he had a duty to raise the people to the level of the elite rather than going down to the level of the masses himself, which again had major implications for his future policies as the leader of modern Turkey.

Mustafa Kemal was also a follower of the wider ideological currents of his time. His generation, the Young Turks being the primary example, adhered to an ideology called Vulgarmaterialismus, which was a popularized version of materialism, combining a materialist worldview with scientism and Darwinism. Influenced by Ludwig Buchner’s Kraft and Stoff, they had faith in science as a cure for all the ills of the Empire and desired the creation of an irreligious, rational society that would represent the triumph of rationality over religion.

Studying Kraft und Stoff as well as the works of French philosopher Jean Marie Guyau, Mustafa Kemal also came to hold a firm belief in the transformative power of science. The ultimate conclusion he drew from these works was the idea that “science promoted progress, while religion retarded it.”4 And once he was in a position of power as the head of modern Turkey, he strived to put these ideas into action.

After World War I, Mustafa Kemal assumed the leadership of the Turkish nationalist movement in the War of Independence (1919-1922). During this time, he adopted both a religious/Islamist and communist rhetoric although, in reality, he despised both ideologies. The reason he felt compelled to pay lip service to these two strands of thought was to ensure the support of Turkish conservatives and the Indian Khilafat movement on the one hand, and the Bolsheviks on the other. In essence, he briefly assumed the identity of a “Muslim communist.”5

Hanioğlu argues that Mustafa Kemal did not have a strong theoretical knowledge of politics or administration in general. He was an admirer of the French Revolution, and his political views consisted mainly of a combination of “republicanism” and “populism” (although only a top-down version). The most concrete representation of his political disposition was the Turkish National Assembly, which he shaped in line with revolutionary France’s “Assemblée nationale constituante,” with legislative, executive, and judicial powers unified under one body. Through this Assembly, Mustafa Kemal sought to implement his project of transforming Turkish society according to the beliefs and ideas that he held.

By the fall of 1922, the War of Independence was won, and Mustafa Kemal, as the undisputed leader of the Nationalist movement, was finally in a position to put his ideas into action. His main goal, true to his intellectual development, was to create a nation-state based on Turkish nationalism, secularism, and scientism. The policies he implemented in subsequent years, such as abolishing the sultanate (1922) and the caliphate (1924), and the proclamation of the Republic (1923) were all steps taken in this direction.

Hanioğlu demonstrates that scientism formed the backbone of Mustafa Kemal’s policies, providing the framework for his secularism and views on Islam. His primary goal was to replace religion with Turkish nationalism by reinterpreting Islam “from a Turkish nationalist perspective.”6 He knew that religion was rooted deeply in Turkish society and that it could not simply be brushed aside. Instead of attacking it head-on, Mustafa Kemal tried to instrumentalize religion as a tool for his modernizing program. He hoped that by reforming and Turkifying Islam, he could create the conditions for the birth of a “Turkish renaissance.”7

The creation of the Directorate of Religious Affairs was a major step towards this direction. Taking up the idea that “Religion is the science of the masses, whereas science is the religion of the elite,”8 Mustafa Kemal believed that a “reformed” Islam would eventually lead to the creation of a society guided by scientism and Turkish nationalism, with religion’s role in society gradually fading away. In this notion, Mustafa Kemal was guided mainly by the French idea of “laicism,” aiming to restrict religion’s role in the public sphere and redefine it strictly as a private matter.

According to Mustafa Kemal’s plans, a new civic religion would eventually take the place of Islam in society, an idea based on Durkheim’s concept of moralite civique.This new civic religion would be a “modified, scientifically sanctioned version of Turkish nationalism,” based on scientism, racial ideas, and Darwinist theories, and play a key role in the creation of a new Turkish identity.9

One of the most important steps taken in this vein was the creation of the Turkish History Thesis and the Sun-Language Theory. These frameworks were based on the works of various scholars from the late 19th and early 20th centuries and aimed at infusing “Turkishness” with a sense of greatness and pride, arguing that the Turks not only founded the world civilization but also disseminated it to the world. They also gave short shrift to the Ottoman past, depicting it as a time of backwardness and decay.10 .

While working hard on his project to create a new Turkish society, Mustafa Kemal did not want his ideas to become an ideology or dogma; however, this is exactly what ended up happening. After his death in 1938, a right-wing interpretation of Mustafa Kemal’s views became the backbone of the ideology of Kemalism, which advocated for the “transformation and authoritarian developmentalism under a single-party regime,” based on scientism, Turkish nationalism, and a personality cult.11

In the last part of his book, Hanioğlu argues that the true aim of Mustafa Kemal’s reforms was to integrate Turkey firmly into the West. Even though the Ottoman Empire lost most of its European territories, Mustafa Kemal held the firm belief that modern Turkey should be a part of Europe. For him, Western civilization was universal, and “any aspects of local non-Western culture that clashed with [it] should be eliminated.”12

In line with this idea, Mustafa Kemal also rejected the notion of a “non-Western modernity.” Seen through this lens, various policies that he implemented as a part of his social engineering project, such as the hat reform, adoption of surnames, or adoption of the Latin alphabet, should be seen as his way of infusing “civilization” into the Turkish society and make it culturally European. These efforts were not totally successful. They were also “far from being a complete failure,” however, with a considerable percentage of the Turkish population today continuing to identify Turkey as belonging to Europe.13

Hanioglu’s Ataturk: An Intellectual Biography does a good job of taking Mustafa Kemal off the pedestal he is usually put on and situating him within the historical context. Acknowledging the crucial role he played in the foundation of modern Turkey, Hanioglu nevertheless argues that Mustafa Kemal was still very much a product of his social, intellectual, and cultural environment.

Mustafa Kemal was not a philosopher or a theoretician per se, but he was an avid reader who was much in tune with the cultural currents of his time and utilized a range of ideas in his efforts to create a Turkish nation-state and forge a new Turkish identity.

The ideas Mustafa Kemal championed as the leader of modern Turkey were already well-known among his peers. What differentiated him from the other late Ottoman reformers was that he could actually put these ideas into practice while he was in a position of power. He also had no qualms about getting rid of the “old” way of life while replacing it with the new. Overall, Hanioğlu makes an important contribution to the extensive literature on Mustafa Kemal. Anyone who would like to understand the roots of how Mustafa Kemal became who he was should definitely read this work.

Thank you very much for reading. If you enjoyed this post, please consider hitting the “heart” button and sharing it with anyone who might be interested. And if you’d like more articles on different aspects of the Ottoman Empire, please subscribe to this newsletter. Your support means a lot!

Şükrü Hanioğlu, Ataturk: An Intellectual Biography (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), 6.

Ibid.

Ibid., 25.

Ibid., 53.

Ibid., 104-105.

Ibid., 132.

Ibid., 153-156.

Ibid,, 152.

Ibid., 161.

Ibid., 165-181.

Ibid., 192.

Ibid., 204.

Ibid., 224.

Looking forward to a future article on why “a new civic religion would eventually take the place of Islam in society” wasn’t fully realized

Thank you very much for this. I have always found Atatürk completely fascinating partly due to the admiring biography by Kinross. Although I read it several years ago, I remember reading about some of Atatürk’s projects in disbelief, in particular the reform of the language and alphabet which I would love to read more about. I also visited his museum in Thessaloniki and the Military Museum in Istanbul where he features prominently. It must be hard to write a biography of such a person and not flinch at describing their lesser qualities. Do you think Hanioğlu managed it well?